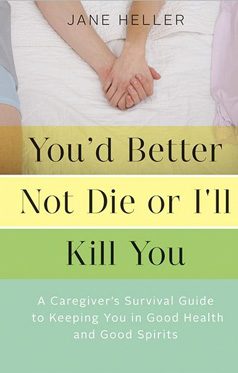

- Publisher: Chronicle Books

- Available in: Paperback, eBook

- ISBN: 978-1452107530

- Published: October 31, 2012

Interviews & Appearances

Listen to Jane on the Caregivers With Hope radio show – September 18, 2017

Listen to Jane on The Women’s Eye Radio Podcast – August 29, 2017

Listen to Jane’s interview with Micheal Pope, CEO of ASEB/Alzheimer’s Services of the East Bay and host of “Life Is a Sacred Journey”

Read Jane’s Interview with the Women’s Eye Online Magazine

Listen to Jane on The Women’s Eye Radio Podcast – February 13, 2013

Listen to Jane on David McMillian’s Podcast on 710 KEEL Shreveport, LA

Advance Praise

This book is the perfect companion for every caregiver. You only have to read the Table of Contents to know Jane Heller has given you the gifts of comfort, humor, strength and solidarity. Take it to the waiting room and always keep it within easy reach! Pauline Jones – RN, Chief Operating Officer, Visiting Nurse & Hospice Care of Santa Barbara

Jane’s book is so engaging and entertaining. She tells her own caregiving story, and provides insights into everything from siblings to doctors to hospitals. Great read! Barbara McVicker – Host of the PBS Special “Stuck in the Middle: Caring for Mom and Dad” and Eldercare Author

Jane Heller’s humorous and compassionate book has real-world advice for caregivers of all kinds, covering topics from diet and exercise, to surviving long hours in hospitals and being taken seriously by medical providers. Jane even covers topics others don’t, such as the sex life of the caregiver, and finding humor and the silver lining in a world of despair. With input from experienced caregivers, it’s a must-read for all who face this daunting task. Susan Disney Lord – 2012 Alzheimer’s Association Southland Chapter Caregiver of the Year

A combination of autobiography, anecdotes from other caregivers, and interviews with experts, this gem of a book makes good on its promise. Written in a no nonsense style with a healthy dose of humor, it offers a wealth of advice on everything from navigating the healthcare system to getting more sleep to the importance of human touch. It’s a valuable resource for caregivers – whether taking care of someone with a stroke, Crohn’s disease, dementia or many other conditions. I recommend it highly. Marie Marley – author of the award-winning Come Back Early Today: A Memoir of Love, Alzheimer’s and Joy

Jane Heller takes us on her heartfelt, humor-filled journey caring for her husband, channeling Nora Ephron along the way. This is a must-read eye witness account of what it takes to care for a loved one and how to keep your spirits lifted in the process. Sherri Snelling – CEO, Caregiving Club

Reviews

You’d Better Not Die or I’ll Kill You Book Review

June, 2017

By Marilyn Willison

Creators Syndicate

Full disclosure; Even though I’ve been obsessed with health issues my entire life, I’ve never been interested in working in the medical field. Most of my classmates from my all-girls high school chose nursing as a career, but I was so freaked out by hospitals and illness that I was the only teenager in my class to actively boycott working as a Candy Striper.

But life has a funny way of catching up with you. So here I am, more than five decades after my high school graduation, firmly in the throes of a family medical situation in which I am a Caregiver. Unfortunately, my husband is battling lung cancer, and I—for the first time ever—have an adult who looks to me to make sure that everything from appointments to comfort level to dietary restrictions to medications are maintained and observed.

Because I am so clueless about the role of a Caregiver, I did what I always do when I need help—visit my local bookstore. Fortunately, I found exactly what I needed in a comprehensive—but lighthearted—book that was written five years ago, You’d Better Not Die or I’ll Kill You; A Caregivers Survival Guide to Keeping You in Good Health and Good Spirits by Jane Heller (Chronicle Books, $18.95, 288 pp).

The reason I found this book so useful, is that Jane Heller—a successful author—wisely avoided the “You need to do A, B, C, etc.” syndrome of lecturing the reader about the right way to care for a loved one. Instead, she shared three helpful resources; her personal experiences of helping her husband cope with a chronic case of life-threatening Crohn’s disease, the insights of other non-medical individuals who had cared for an ill loved one, and advice from a variety of health-care professionals.

Not everyone in Heller’s book is dealing with a sick spouse. “Dear Abby” columnist Jeanne Phillips tells about the conflicts that arise when a parent is older and ill. And we also learned about the challenges involved when caring for a sick child. So why did a successful author of romantic comedies tackle such a daunting subject? “I wanted to help all of us take care of ourselves so we’re able to take care of those we love…. I wanted to express (and encourage you to express) the emotions we all have when caring for a loved one but are often too guilt-ridden, fearful, or embarrassed to say what’s really on our mind’s….I wanted to reach out to other Caregivers…and let them vent or offer inspiration or serve up a helpful tip or two….I wanted to be the cheery, knowledgeable companion I wish I had had [when in my husband’s hospital room].”

According to the National Family Caregivers Association, 40 to 70 percent of caregivers exhibit some form of clinical depression. And if you are caring for a spouse your symptoms of depression or anxiety maybe as much as six times higher than that of non-caregivers. If you are caring for a parent, that rate will be twice as high as for non-caregivers. This is important information because close to 70 million Americans are currently Caregivers, which means that about 29 percent of the adult population in the US is walking around feeling stretched and pulled in a variety of different directions.

The one thing I’ve learned so far about being my husband’s Caregiver is that my disappointments, fears and tears will not help his situation. My job right now is to be fully in control and completely in the moment. If I hadn’t avoided the Candy Stripers back in 1966, I probably would have known that already!

An Enlightening Tale of Caregiving

Aug 7, 2013

By Marty Bell, National Aging in Place Council Age in Place Newsletter

Author Jane Heller is a literary entertainer whom, after 13 comic novels, has taken on as a subject the anguish of providing care to a loved one and yet somehow manages to tell her non-fiction compassionate tale with the humor that is her trademark. In You’d Better Not Die or I’ll Kill You: A Caregiver’s Survival Guide to Keeping You In Good Health and Good Spirits, Heller takes us through nearly 20 years of the practical and emotional struggle of being right there at every moment for her husband Michael as he battles Crohn’s disease. Jane and Michael are very brave people and reading their story–a love story set against the romantic backdrop of hospital wards–will make you feel braver.

I confess Jane and I have been friends for more years than she would want me to tell. (Hint: We attended an Ali-Frazier fight at Madison Square Garden together.) And I have watched her evolve as a skillful storyteller with great admiration. From early on she has been a perspicacious observer of behavior, both other peoples’ and her own. But in this book she reaches a level of raw honesty, often at her own expense, that I find rare and moving.

“I wanted to express (and encourage you to express) the emotions we all have when caring for a loved one but often too guilt-ridden, fearful, or embarrassed to say what’s really on our minds,” Heller writes. And she doesn’t hold back. Emotions fly at you; responses to doctors, nurses, supposed friends, family who should know better, healers, dealers, religious shpielers, even Michael. And all of it accompanied by a chorus of other amateur caregivers sharing their own emotional battles.

Caregiving is a topic du jour as the Boomers approach that age while still supporting children finding their way and parents living longer than anyone imagined. We’re told 70 percent of aging Americans need in-home care at some point, but who’s going to supply it? All of us, apparently–making You’d Better Not Die or I’ll Kill You a mandatory read.

Library Journal Xpress Reviews: Nonfiction | First Look at New Books

Fri Feb 22, 2013

By Richard Maxwell, Porter Adventist Hospital Lib., Denver

The worst-paid job in health care offers among its benefits the longest hours, the fewest days off, and the most consistent stress. Caregivers include the family members or good friends who are there for those with chronic illness, the disabled, and the dying. Novelist Heller (Female Intelligence), now a caregiver to her husband, explains that she, like many others, didn’t choose the role but slowly adapted to it. Here she discusses practical problems and emotions that caregivers of all types face and offers suggestions for coping. She goes beyond her personal experiences by including comments from other caregivers she’s come to know, calling them the book’s Greek chorus. Candid interviews with professionals whom unpaid caregivers sometimes view as adversaries offer useful perspective. Tips range from the pragmatic, such as how to deal with time in a waiting room, to the profound, as in the chapter “Getting Through the Goodbye.”

Verdict: Writing with humor and a relaxed style, Heller has produced a valuable, virtual support group in book form that could be beneficial to any caregiver.

Dawn Marcus, M.D.

December 19, 2012

A lot of attention is given to coping with chronic illness. Sometimes we forget that not only is the patient coping with limitations, discomfort, and frustration. Caregivers also can be profoundly affected by the illnesses of those for whom they’re caring.

In You’d Better Not Die or I’ll Kill You, Jane Heller gives a voice to those many hardworking, sacrificing caregivers who have previously often been neglected.

When Heller married, she knew her future husband had Crohn’s disease, but couldn’t comprehend or imagine the impact those two little words would have on their years together as she shifted from girlfriend to caregiver. Heller helps validate common feelings and frustrations and lets you know you’re not alone. She openly discusses conflicts with healthcare providers, family, and friends and frustrations when your partner’s personality seems to change or you feel guilty going to work instead of staying with your loved one. She includes stories of other caregivers, so you’ll likely find stories similar to yours. Heller also offers sound practical advice for coping with the added difficulties of being a caregiver:

– Specific questions to ask to help you communicate with your doctor

– Sleep tips for caregivers

– Figuring out when it’s time to see a mental health specialist

This book will truly be a blessing for those many caregivers who often feel frustrated, angry, misunderstood, and guilty. This book will be an affirmation to let you know you’re not alone, that your work is incredibly important, and that there are effective strategies other caregivers have found helpful that might also be applied to help your situation be a bit easier to bear.

Spousal Care book by Jane Heller – great read!

Fri Nov 30, 2012

By Lawrence Bocchiere III, President “The Wellspouse® Association”

As president of the Well Spouse Association I read and review many books on caregiving. In our organization we have our own face-to-face support groups, reminiscent of the groups appearing in vignettes in this book. The book is absolutely wonderful….Though many such books are informative, I have never ENJOYED reading a book about caregiving before! Ms Heller uses humor to mitigate pain; and the vignettes from her ‘support group’ closely mirror the actual discussion that occurs on any subject in Well Spouse face to face support groups! I highly encourage tired caregivers and those that could become caregivers to take the time to read this book. You will be glad you did.

Publisher’s Weekly (starred review)

November 5, 2012

Novelist Heller (The Secret Ingredient) is no stranger to illness; her father had brain cancer, her stepfather had complications from epilepsy, and she married a man with severe Crohn’s disease. So readers might assume, Heller acknowledges, this is a “bad news book.” But it is actually candid, informative, upbeat, and sometimes ribald. Heller discusses complex but essential topics—such as making nurses your friends and the competing demands of work and caregiving, frequently via mini-interviews with a relevant professional, such as an ER doctor (who explains why ER waits are so long), ICU nurse (“family members become our patients in a way”), or attorney (on getting patients to sign essential legal documents like advance directives). Her breezy tone strikes just the right note for difficult subjects like wishing your loved one would “disappear” and more practical discussions like why cooking for oneself is important. The array of perspectives adds a richness to the discussion. It’s impossible to write a book like this without addressing the emotional issue of saying good-bye, but Heller characteristically follows that with an upbeat “silver linings” chapter. This is a useful book for patients and caregivers alike. (Nov.)

Inspiration

I was spending an afternoon with Leigh Haber, my friend and the editor of my “She-Fan” book, and I said, “What are you working on these days?” She replied, “I’m acquiring wellness books for Chronicle.”

Wellness books, I thought. I can write one of those.

Of course, I had no idea what a “wellness book” was, except maybe a guide to dieting or exercising or even meditating? And then Leigh explained that the genre can include all sorts of topics – from health care to creativity – and that she was looking for books that would spark discussion and find an audience that could relate.

I flashed back to the previous year when my husband Michael, who has a chronic illness called Crohn’s disease, was hospitalized numerous times and had two major surgeries, and how I’d been pondering our 20 years’ worth of adventures involving his being sick and my being his caregiver and how that dynamic had impacted our relationship. At the same time, my mother was well into her ’90s and having memory problems, and my sister and I had been concerned about her living at home alone. And then I thought about all the different ways people are being called to action as caregivers – parents caring for a child with an illness or disability, wives caring for husbands and partners who are sick or (or vice versa), baby boomers caring for their aging parents, military families caring for an injured soldier. I’d read that there were an estimated 65 million caregivers in the U.S. alone, and I found the statistic staggering.

“Leigh,” I said. “I’d like to write a wellness book for you. Interested?”

Fortunately, she said yes and we came up with a hybrid – part memoir, part how-to that would be both personal and prescriptive. I really hope the book will be a supportive “pal” to anyone going through the caregiving experience.

Introduction & First Chapter

Introduction

“I can’t take the pain!” Michael wailed. “Just get a gun and shoot me already!”

My then-boyfriend-now-husband scared the hell out of me that day in 1991, both because he wasn’t the type to wail and because he was suggesting that I do something pretty Kevorkianesque. In the eight months since he’d moved into my Connecticut house, I had never heard him raise his voice, much less beg for assisted suicide. Besides, I didn’t own a firearm, not even one of those benign-looking mini-revolvers you can carry around in your handbag like a BlackBerry. The one and only time I fired a gun was during a college fraternity party at a “gentleman’s farm” in Virginia. Everyone was taking part in something called skeet shooting, which, as a Jewess from Scarsdale, was as foreign to me as doing my own nails. My date showed me how to hold the rifle, I pulled the trigger, and I was blasted backward with such force that the hole in the ground is probably still there.

“Should I call an ambulance?” I said to Michael, not having a clue what I was supposed to do. I was a writer, not a doctor, and my nurturing skills were nonexistent. I didn’t have kids. I didn’t have pets. I didn’t even have plants except for polyester ones, and even they looked wilted.

All I knew was what Michael had told me early in our courtship (in the most offhand, who-cares way) that he had something called Crohn’s disease, which, I later learned, is an autoimmune disease of the gastrointestinal tract whose trademarks are—wait for it—abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, rectal bleeding, intestinal blockage, osteoporosis, neuropathy, skin rashes, clubbing of the fingers, and severe depression. Since he had exhibited virtually none of the above atrocities and assured me that he’d been in remission for years, I paid little attention back then. We were in love, wildly attracted to each other, eager to be married and begin our sure-to-be-blissful future together.

Clearly, I was delusional.

“No ambulance!” yelled Michael. “Do you hear me?”

They could hear him in Azerbaijan.

He continued to thrash around on our living room sofa and I continued to circle him as if he were an explosive about to go off, and our housekeeper, an extremely focused Peruvian woman named Maria, continued to vacuum the carpet under our feet since it was her day to clean and I hadn’t canceled, due to the sudden onset of Michael’s condition.

“I’ll take your temperature again,” I said, feeling the need to do something, anything. I grabbed the thermometer and stuck it under his tongue. The verdict: his fever had spiked to 105.

“I’m so cold,” he said, shaking now, convulsing.

Enough was enough. Even a dip like me knew it was time to call 911.

As Maria and I waited for the EMT guys, I tried to figure out what, exactly, had happened to my beloved. It was his head that was killing him, not his gut, and he said he felt as if someone had broken his legs. The fever could be causing the head and body aches, but what was causing the fever?

And then it hit me: the pills he’d been taking for the past month. He’d gone to a new gastroenterologist who’d put him on a drug called 6-MP. Could he be having a reaction to the medication?

I offered up my theory to the EMT guys when they arrived. They nodded and called me “ma’am” and looked like a cross between firemen and backup dancers for Lady Gaga, but they were more interested in swaddling Michael in blankets and lifting him onto a gurney than in listening to my chatter.

I backed away, gave them space, and wondered what I’d gotten myself into.

Growing up with a mother who had nursed two sick husbands (my father had brain cancer, my stepfather had complications from epilepsy), I had vowed to marry for health—to avoid being saddled with a mate who would require me to become that most dreaded of all things: a caregiver. What I’m saying is that the last—I mean, the very last—thing I was looking for in a man was a medical flaw. I would rather have married a crocodile.

Not that I didn’t admire my mother’s devotion as well as her lack of squeamishness when it came to seizures, bedpans, and vomit. (I had a thing about hurling—was terrified of doing it, being around someone doing it, even sitting through a movie in which someone was doing it.) I thought she was heroic, really I did, but I had no desire to follow in her footsteps. I had seen entirely too much dropping dead on the part of men and was looking for a guy who would hang around. When I met Michael, a tanned, lean, physically fit photographer who was so vigorous he had crewed on a 1920s schooner, sailed it to the Caribbean twice, and even survived a fall overboard into the Atlantic during a nor’easter, I said to myself, “Woohoo. Here’s a live one.”

So much for that, I thought now, as the gurney transporting Michael made its way down the stairs and out to our narrow street—at the very same moment that an extremely large van pulled up to the house.

“Heller residence?” the driver called out the window.

My heart lurched. I had completely forgotten about the boat—the do-it-yourself kit for a little wooden dinghy that I’d ordered from Wooden Boat magazine as a surprise for Michael’s birthday. He’d been eyeing it for weeks and I couldn’t wait until it came. I just didn’t expect it to come while he was being carted off to an emergency room.

I jumped into the street and started directing traffic and tried not to have a nervous breakdown. I convinced the driver to unload the boat and leave it in the garage under Maria’s supervision, then climbed into the front seat of the ambulance, and sped away to the hospital.

Michael was in the back being “worked on,” and I kept craning my neck to check on him. And then I started crying—loud, heavy, ridiculously wet sobs—and blubbered, “Please tell me he’ll be all right.”

“Don’t worry,” said the ambulance driver, becoming the first person to utter what would become a lifetime of “Don’t worry’s.”

There was more fun to be had at the hospital. Since cell phones weren’t as commonplace as they are now (plus they were the size of suitcases), I had to call Michael’s gastro doc from a pay phone in the emergency room. I didn’t reach him, naturally, because he was a Very Important Doctor, but his resident took my call.

“Could it be a reaction to the 6-MP?” I asked.

“Doubtful.” He chuckled derisively, as if I’d just asked him if cigarettes were good for you. “It doesn’t present that way.”

“Well, it did present that way,” I said.

“Let’s see what happens when he’s off the drug,” he said.

What happened when Michael was off the drug was that I had been correct in my diagnosis: his fever vanished along with his body aches and it was, indeed, the 6-MP that had caused a reaction.

“Thanks for taking such good care of me,” Michael said as he was being discharged.

“No big deal,” I said, not in an attempt to be modest but because I wanted to block out the whole episode and go back to being a garden-variety woman in love.

Good try, Jane.

I had lost my caregiver virginity and there was no going back.

Crohn’s, it turned out, was hardly “no big deal.” Michael had been hospitalized nearly seventy-five times before I met him and was, in hospital parlance, “a frequent flier.” He’d had intestinal obstructions and complications from surgeries and, as if Crohn’s wasn’t nasty enough, he got kidney stones a lot—like often enough to gravel a driveway. Oh, and did I mention that all he did was vomit? If there were a reality show called American Hurler, he’d win by a landslide.

I was tempted to bolt upon learning all these tidbits. I was tempted to tell him to bolt. I was tempted to say, “Sorry, dude, but I’m not cut out to be the wife of a man with all your medical issues.” (Okay, I wouldn’t have used the word dude back then. I wouldn’t have used the word issues either; white men from Fairfield County weren’t dudes and issues were known as problems.)

I should add here that I’d been married twice before, speaking of bolting.

My first husband was a charming guy with whom I’d gone to high school. We were young. We played a lot of tennis at the country club where both our families were members. We invited other similarly overprivileged couples to our Manhattan apartment for fondue. We were divorced within a year because we both realized that we had merely entered into a Starter Marriage and there was no point in pretending otherwise.

My second husband was a grownup—a divorced professional with two young children and a sweet disposition. We got together during the Greed-Is-Good ’80s, built a 6,000-square-foot house in the suburbs, traveled to sprawling resorts of the type that offer villas with private “plunge pools,” and dressed well. When the stock market went bust, so did our marriage.

And then I met Michael, who didn’t have money but did have health (or so I thought). I predicted to anyone who’d listen, “Third time’s the charm.” What could possibly go wrong this time?

When I found out about his Crohn’s—really let it sink in that we were talking about a chronic illness that would not only never go away but would probably get worse—I saw my life flash before me. (For some reason, these life-flashing-before-me fantasies were like clips from classic Bette Davis movies; I would gaze at Michael and deliver a line from, say, Now, Voyager: “Oh, Jerry. Don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars.”) I saw only tragedy and melodrama, with me as the long-suffering heroine.

But instead of bolting, I burrowed in. I suckered myself into thinking our romance was so special that our “happy vibes” would bolster his faulty immune system, that he would thrive once we were legally bound to each other, that love really would conquer all. And so, in the face of the evidence, I married him.

Over the next twenty years, Michael and I settled into a pattern. He’d suffer through his hospitalizations and/or surgeries (uncannily occurring over national holidays when doctors are playing golf in Palm Springs or skiing in Aspen or frolicking with their kids at Disneyland), and I’d be his stalwart helpmate. I’d drive him to various ERs while he barfed into garbage bags, sit in surgical waiting rooms listening to the life stories of people I’d never see again, and call concerned friends and family members as soon as I got home. To the outside world, I was a saint—my mother’s daughter. In private, I was cursing Michael for leaving me over and over again, resenting him for disrupting my work routine, hating him for depriving me of the kind of normalcy I was sure every other couple was enjoying.

Who was this person? One minute he was the handsome, gentle man I’d married; the next he was pumped up with steroids, bloated and moonfaced, screaming obscenities, and punching walls. One minute I was praying he wouldn’t die; the next I was hoping he would. He was the perennial patient, but—little did I know—his illness and my conflicted feelings were making me sick.

Okay, why is she telling us all this, you’re probably asking yourself if you’ve bothered to read this far? Or, perhaps, you’re asking: Does the world really need yet another book in support of the noble, compassionate, utterly frazzled people who care for loved ones with health problems? Don’t we already have dozens of titles on the subject—elegiac illness memoirs, thought-provoking treatises on death and dying, imposing reference volumes full of resources, not to mention perky self-help manuals that teach us how to clip our elderly, dementia-impaired parents’ toenails? And aren’t there a million websites and blogs that offer more advice than a caregiver could possibly have time to digest?

All very valid questions, and I’d be asking them myself.

So here’s why I wrote this book despite all the others out there:

I wanted to add my two cents, chime into the conversation, move off the sidelines, because the subject is too important for me to remain a detached observer.

I wanted to share my adventures in caregiving—what’s worked for me as well as the mistakes I’ve made—and enlist experts to show me (and you) how we can do things better.

I wanted to help all of us take care of ourselves so we’re able to take care of those we love—from how to get the proper exercise to how to get a decent night’s sleep. And, trust me, I’m not coming at this from some preachy, soap-boxy point of view. I used to roll my eyes at all the well-meaning people who kept telling me to stop neglecting my own health—until I could no longer ignore what was happening inside my body. I ended up going from caregiver to caregivee, thanks to several skin cancer surgeries and a hysterectomy, but I was lucky to have a spouse who was eager to switch places and take care of me for a change.

I wanted to express (and encourage you to express) the emotions we all have when caring for a loved one but are often too guilt-ridden, fearful, or embarrassed to say what’s really on our minds.

I wanted to reach out to other caregivers, including a few whose names you’ll recognize from movies, television, and publishing, and let them vent or offer inspiration or serve up a helpful tip or two. I’ve never joined a support group in all the years I’ve been a care- giver, so talking to them during the interviews they were generous enough to give has allowed me to feel as if I’ve started a little group of my own.

I wanted to ask, “Is this normal?” in a variety of caregiving situations—and get the answers. Is it normal to be intimidated by doctors, to be flummoxed by the health-care system, to be mad at your sister, to wish you could rewind your life? How do we know what’s normal unless we have specialists to tell us? This book has specialists.

I wanted you to laugh. No surprise there if you’ve ever read any of my novels, which are comedies and demonstrate my firm belief that humor gets us through even the bleakest hours. That’s where the title of this book comes from: the part of me that makes jokes. Whenever Michael would be wheeled into the operating room and one of the surgical nurses would stop the gurney just before it arrived at those scary-looking double doors, turn to me and advise, “Sorry, but you’ll have to say your goodbyes here,” a giant lump would form in my throat, tears would prick at my eyes, and instead of grabbing her by the collar of her blue scrubs and screeching, “No! Wait! Please don’t take my husband away!” I’d lower my face close to Michael’s, give him a kiss on the mouth, and crack, “You’d better not die or I’ll kill you.” He’d laugh and so would the nurse, and then off he’d go.

I wanted to give you a book that would be a pal for life, without judgment, without strings, without pre-existing conditions—a book that you could pick up and read at any point, on any page, and find something useful. In other words, I wanted to be the cheery, knowledgeable companion I wish I’d had when I was sitting in Michael’s hospital rooms, sliding off those uncomfortable chairs, smelling hospital smells, hearing hospital sounds, feeling hopeless and alone and sorry for myself. There’s a chapter coming up about friendship—how people often drift away when a family member has a chronic or progressive illness. This book won’t drift away. It won’t stop calling or forget to ask how things are or say, “We must get together,” and then never follow up. It will be there for you whenever and wherever you need it.

Sound like a plan? Good.

CHAPTER 1

What Is a Caregiver Anyway?

“I used to be cute before all this caregiving. Now I look like I’m a hundred.”

—BARBARA BLANK, caregiver

Here’s a little quiz. If you answer yes to any of the following questions, you’re officially a caregiver and I salute you. Well, maybe a salute doesn’t do us justice; we should probably have a secret handshake—something cool where we slide our palms together, grab hold of our thumbs, and finish up with a fist bump.

Have you ever said the words “I can’t take it anymore?” More than once, in fact?

Have you fantasized about flying to Fiji—by yourself?

Have you spent an inordinate amount of time engaged in imaginary conversations with doctors in which you ask all the things you intended to ask but didn’t?

Have you fallen asleep at your desk, snapped at someone in a supermarket checkout line, or cried in the bathroom?

Have you had the thought: “I should be getting paid for this?”

Have you looked in the mirror and wondered if you’ve always had those craters under your eyes?

Have you jumped when the phone rang and actually felt relieved when it was a telemarketer?

Have you worn enough Purell to disinfect an entire third world country?

Have you said about a hospital cafeteria: “Why are the trays always wet?” Or: “That chicken gumbo wasn’t as bad as it looked.” Or: “Does Melba toast still have to taste like cardboard after all these years?”

Have you worked up a nice, simmering resentment toward a sister or brother who tends to leave all the heavy lifting to you? Or, conversely, have you been weighted down by guilt because you aren’t the daughter/son who lives in the same town as Mom or Dad?

Have you wondered why the patient in the bed or room next door to your beloved always has the TV on too loud, not to mention tuned to The Price Is Right?

Have you gotten tired of people telling you to “hang in there”?

Has your heart swelled with affection for a nurse or an aide who acknowledged your existence?

Have you made a morning vow to get more exercise— only to slip into bed at night and say hopefully, “Maybe tomorrow”?

Has your upper lip ever started twitching for no apparent reason?

Have you told yourself it’s okay to eat that entire bag of Doritos Nacho Cheese Flavored Tortilla Chips in one sitting because you’ve “earned it”?

Are you on a first-name basis with the guy at the pharmacy?

Do you yearn for the days when your loved one was healthy enough to piss you off?

So tell me: How’d you do on the quiz? Did anything on the list ring a bell? At least one thing?

I bet you’re nodding. The point I’d like to make here is that caregivers—no matter what our backgrounds and circumstances—have a lot in common. I find that very comforting. I like that we’re all in this together. I feel heartened that, while we all want what’s best for our loved ones, would move mountains on their behalf, and feel tremendously grateful for the time we’re able to spend getting to know them in ways we’d never experience if they weren’t sick, we can still say without the slightest hesitation, “Man, is this the pits or what?”

So yes, caregivers share a mindset. On the other hand, we come in all shapes and sizes and there’s no one single definition; the term is and should be broad.

Some people care for a spouse or life partner.

Some people care for a child.

Some people care for a dear friend or neighbor.

Some people care for an elderly parent or relative.

Some people are on the scene 24/7 with sole responsibility for care.

Some people are on the scene with assistance from a professional companion or health-care worker.

Some people are long-distance caregivers who do what they can from afar.

Some people care for a parent and children simultaneously and are part of the so-called “sandwich generation.”

Some people are pressed into service in fits and starts, the result of the patient’s flare-ups during the course of a chronic illness.

Some people are called upon to serve suddenly and dramatically, following an accident or unexpected crisis.

Some people are simply Good Samaritans who want to help whenever there is a need.

Some people are taking care of someone with a terminal illness.

Some people are riding out a medical condition that will improve over time.

There’s no story that’s “worse” than another; caregiving is not a competitive sport. I like that part too—that we don’t have to play, “Can you top this?” We each appreciate what the other is going through.

There are many ways to be a caregiver, in other words, and there are many of us who fill the role—65 million of us in the United States alone, according to the National Family Caregivers Association, which means that 29 percent of the adult population is walking around stretched and pulled in all directions. I’m glad there’s a name for us now, because there was a time when it wasn’t even in the lexicon.

Take my mother, for instance. My father died of brain cancer when I was six, but what I remember most about my early years was how normal they seemed in some ways. My mother got me and my sister off to school on time, arranged our play dates with friends, and sent us to summer camp, where we learned how to make potholders and ashtrays and whistle lanyards—all while my father suffered one medical crisis after another. She “juggled well” is what people said about her, since this was the 1950s, when there were euphemisms for just about every sort of unpleasantness.

And then he died and she fell apart. She became convinced that she, too, had a brain tumor, only to be told by each doctor she consulted that she was exhausted from years of looking after my father. She was suffering from a classic case of “caregiver burnout,” another term nobody used back in the day.

Three years later, she met and eventually married my stepfather, a widower with four kids. He was the picture of health—a strapping, broad-shouldered former collegiate track-and-field star who happened to have epilepsy. At first there were merely the seizure-related mishaps—a broken jaw, a cracked rib, reactions to medications. Then came more serious complications and a long, steady decline. My mother remained in caregiver mode through it all—even as she raised four stepchildren along with my sister and me and worked part time as a professor of Greek and Latin. After he died, she felt lost again. Caregiving had been her “job,” her purpose. She was almost too good at juggling.

There was no appropriate term for me either when Michael was hospitalized with an intestinal obstruction in the early ’90s—the first such episode since we’d been together.

“Are you his wife?” asked the nurses, the doctors, the insurance lady, even the guy who came to draw his blood.

“Girlfriend,” I’d tell them all and wait for The Look. I was the only one there, the only one who stuck around, the only one who contacted his siblings and brought him his boating magazines and helped him figure out how to work the arcane TV remote—and yet “girlfriend” didn’t cut it, judging by their air of dismissal. I might as well have said I was a hooker he’d picked up off the street. (Important note: The role of girlfriend is perfectly respectable nowadays and you can be thoroughly in charge of your loved one’s care—provided you are so designated in a power of attorney document.)

The fact that I lacked a suitable title really rattled cages when I appeared at the hospital outside of permitted visiting hours. Girlfriends weren’t considered immediate family back then, so there were times when I had to muscle my way in.

“What are you doing here?” a nurse asked when I showed up in Michael’s room one morning before seven.

“Visiting the patient,” I said.

“Are you his wife?”

“No.”

“Sister?”

“Nope.”

“Then you shouldn’t be here.”

“Let me ask you something,” I said, trying to remain calm and polite. “Do you want him pressing the ‘call’ button every six seconds? Or would it make your life easier if I handled the simple chores?”

She scowled, put her hands on her ample hips. She was a boxy woman with a not-so-faint-mustache, and I could easily picture her serving as a prison warden. “Rules are rules, and—”

“Let me ask you something else,” I interrupted, figuring a new tactic was in order. “Have you ever been in love?”

“Excuse me?”

“In love. You know.”

Her expression softened. “As a matter of fact, I’m getting married in three months.”

“Congratulations!” I said, reaching for her hand and pumping it vigorously. “Have you picked out your dress?”

Well, that did it. Get a woman talking about her wedding and she forgets to be mad at you.

She described the dress, the bridesmaids’ dresses, the flowers, the cake, blah blah blah. She was my new best friend and by the time she left I could have shown up at the crack of dawn and it would have been okay.

Not that I was always so charming. During that same hospital stint, I had asked Michael if he’d be okay without me for a day. The two-hour drive between Connecticut and Manhattan was wearing me down and I was desperate to get back to the novel I was writing, not to mention have some quiet time to myself. He said he understood and I was grateful.

About two hours into my solitude, I called him to check in.

“Everything okay there?” I asked.

“I’m really cold,” said Michael, his voice tremulous, near tears.

“What do you mean, ‘You’re really cold’?” I said, assuming he was just “in a mood.” He was on high doses of medication, including prednisone, and his emotions were all over the place.

“I can’t get anyone to give me a blanket and it’s freezing in here. I pressed the call button for the nurses, but no one will help me.”

It’s a cliché to write, “Smoke came out of my ears,” but that’s exactly what I felt like when he said that: mad enough to breathe fire. Michael is the antithesis of a complainer; he could be bleeding from his eyeballs and he’d tell you he was fine.

“I’ll be right there,” I said.

I made it to the city in record time. I parked near the hospital, marched inside, rode up in the elevator to Michael’s room, and found him in bed with his pathetic blue windbreaker draped over his shivering body. Oh, and he was right about the temperature: it was a meat locker in there.

“Give me a sec,” I told him and stomped into the hall to the nurses’ station. Have you seen the movie Terms of Endearment? If so, remember when Shirley MacLaine had a meltdown, demanding that somebody give Debra Winger her pain meds? Well, I pulled a Shirley.

“Can somebody give my boyfriend a goddamn blanket?” I yelled, as a handful of nurses stared at me. They looked frightened. I felt ashamed.

“I’m sorry.” I began again, less noisily this time. “I realize you’re busy and this isn’t on the level of a Code Blue, but I shouldn’t have to drive two hours to ask one of you to stop ignoring your patient, who has asked several times for a blanket and not gotten one.”

Michael got a blanket. Actually, he got three blankets. And more ice chips for his dry mouth, a fresh box of tissues, and a lot of plumping of pillows and adjusting of his bed.

I wasn’t proud of my tone or my language or of having to raise my voice, but there are times when you can’t help yourself if you’re a caregiver. Which is what, even though the term wasn’t in widespread usage yet, is exactly what I was.

Over the course of writing this book, I’ve talked to other caregivers whose specific experiences are very different from my own but whose emotions, thoughts, and knack for finding humor in even the grimmest circumstances have mirrored mine. I think of them now as members of the book’s Greek chorus—and as my support group. Let me introduce them.

Yudi Bennett, CA: A former award-winning assistant director in Hollywood whose credits include Kramer vs. Kramer and Broadcast News, Yudi is now a single mother and caregiver to her autistic son after having lost her husband to lymphoma.

Barbara Blank, FL: Barbara is the primary caregiver for her ninety-six-year-old father, who lived with her before moving recently into a nearby seniors’ community. Additionally, her husband suffers from hearing impairment and dementia.

Harriet Brown, NY: A prolific writer and editor, Harriet chronicled her daughter’s struggle with anorexia and her family’s hands-on approach to caregiving in her critically acclaimed book Brave Girl Eating.

Linda Dano, CT: The Daytime Emmy Award–winning actress, talk-show host, and designer of home accessories on QVC, Linda has seen her share of tragedy. She became the caregiver for her father (Alzheimer’s), her mother (dementia), and her husband (lung cancer), and has toured extensively to raise awareness about caregiving and depression.

Jennifer DuBois, VA: Jennifer took a leave of absence from her job as a corporate communications specialist to take charge of the care for her mother, who was dying of bone cancer.

Victor Garber, NY: The versatile Emmy Award–winning star of stage and screen, Victor had two parents with Alzheimer’s. He served as the primary caregiver for his mother while he was in L.A. garnering fans and accolades on the hit TV series Alias.

John Goodman, NY: John’s world changed when his wife of many years was suddenly diagnosed with the rarely understood Cushing’s syndrome and he was catapulted into the role of caregiver.

Judy Hartnett, FL: Judy was no stranger to challenges, having become the stepmother to her husband’s young children when they were first married, but nothing prepared her for her role as his primary caregiver when he was diagnosed with MS.

Deborah Hutchison, CA: A film producer and author, Deborah was called to action when her mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and she became her mom’s primary caregiver. She wrote the innovative and much-needed book Put It in Writing: Creating Agreements Between Family and Friends, which includes the agreement “Caring for Our Aging Parents.”

Michael Lindenmayer, IL: Michael took a year’s sabbatical from his business ventures to help his worn-out parents care for his elderly grandfather. After experiencing the challenges caregivers face, he created the Caregiver Relief Fund, which provides four hours of respite to deserving applicants.

Suzanne Mintz, MD: The diagnosis of her husband’s MS and her experiences caring for him motivated Suzanne to cofound a newsletter for caregivers that eventually grew into the National Family Caregivers Association (NFCA), one of the nation’s go-to resources for education, support, and advocacy.

Jeanne Phillips, CA: Jeanne took over the writing of Dear Abby, the world’s most widely syndicated column, when her mother, Pauline Phillips, also known as Abigail Van Buren, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. She reaches out personally to those who write to the column asking for help with an Alzheimer’s patient.

Suzanne Preisler, NY: When her younger sister was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, Suzanne became her caregiver and most ardent champion, seeing her through a successful ten-year battle. She was called upon again when she learned that her mother had pancreatic cancer.

Karen Prince, CA: Karen’s husband suffered a massive stroke in his forties. Despite his inability to walk or talk, she not only took care of him but also moved them both across the country to California, where they lived for years until he succumbed to lung cancer.

April Rudin, NJ: A busy mother of two children, April nevertheless shared primary caregiving responsibilities with her sister for their beloved grandmother, who lived 3,000 miles away and had Alzheimer’s. She made frequent trips across the country to handle all medical issues.

Harold Schwartz, FL: Harold’s son was in the prime of his life when he was diagnosed with ALS. Harold handled the caregiving on weekends and marveled at how his son never lost hope. He then cared for his wife, who suffered from Parkinson’s.

Toni Sherman, CA: When her daughter contracted a serious foot infection, Toni took care not only of her child but also of her child’s children. Soon after, Toni’s mother received a diagnosis of peritoneal cancer, and her caregiving duties doubled.

John Shore, CA: Christian blogger, humorist, and author of Penguins, Pain and the Whole Shebang, John had a turbulent relationship with his father, from whom he was estranged. But that didn’t stop him from moving into his dad’s house and assuming the role of caregiver when his father needed help after a stroke.

Diane Sylvester, Cissy Ross, Jackie Walsh, and Cecilia Johnston, CA: This group of remarkable women met while their mothers (and Cecilia’s father) were all residents of the Samarkand, a seniors’ community in Santa Barbara, and bonded over their caregiving experiences. Diane’s mother suffered from depression and dementia. Cissy’s mother lost her ability to speak after a series of neurological problems. Jackie’s mother had severe macular degeneration, fell and broke her hip, and suffered a stroke. Cecilia’s mother, the only surviving mom of the four, has Alzheimer’s.

Every member of my new support group will be offering up some of what they’ve felt, thought, and learned over the years since they were tagged with the responsibility of caring for a loved one. They are wise, resourceful, funny, and courageous, and have managed to find silver linings in their darkest moments. I salute them—and give them a fist bump.

Summary

Jane thought she’d found her dream husband in handsome, healthy Michael, a sailor and architectural photographer, until it turned out he’d been hospitalized nearly seventy-five times before they met. Afflicted with Crohn’s disease, Michael wasn’t so healthy after all, and Jane learned that being a caregiver can strain even the most solid relationships.

With her sly wit and novelist’s eye, she shares her experiences – from how to get that cranky surgeon to talk to you (“box the doc”) to why men should never go to a doctor without a woman along (“nagging wives save lives”). Throughout, she consults her “roundtable” of caregivers, such as Emmy Award-winning actor Victor Garber and “Dear Abby” columnist Jeanne Phillips, to answer the question “Am I the only one who feels this way?” Plus, advice from experts brings you the most up-to-date guidance on staying healthy and sane while caring for a loved one. You’ll find tips from meditation teachers, fitness instructors, therapists, even a cookbook author with recipes for stressed out caregivers. Nothing’s off-limits in the book: not living wills, not sibling rivalry, not friendship, not sex.

Whether you’re wrestling with the decision to place Mom in a nursing home or assisted living community, confronting the challenges of having a chronically or critically ill spouse, or coping with the stress of raising a child with an illness or disability, Jane is your trusty companion in this personal and invaluable resource – an irreverent yet always compassionate girlfriend’s guide to caregiving.