Reviews

USA Today

8/1/94

Larry King’s People News & Views

My two cents … Jane Heller’s Cha Cha Cha is a fine first novel that reads like a summer breeze …

Booklist

Reviewed by Mary Ellen Quinn

Alison Koff’s husband, Sandy, tells her that all their money is gone and that he’s going back to his first wife. Alison is left with Maplebark Manor, the 18-room mansion they bought and renovated. The bank is threatening to foreclose, and Alison’s part-time job writing features for the local paper doesn’t pay much, so she puts the house on the market and sets out to find more work. She is annoyed by, and then later attracted to, Cullie Harrington, the photographer who comes to take pictures of her house for the real-estate brochure. Housekeeping is the only job Alison can find, and her employer turns out to be the celebrity-biographer Melanie Moloney, who’s working on a tell-all book about a prominent newspaper owner; Alison has hardly begun work when her boss is murdered. Alison is the prime suspect, but she manages to identify the real killer, discovering some shocking secrets about her own family along the way. She also sheds all the trappings of her upscale 1980s lifestyle and finds love. A bright, lively comedy that zips right along.

Copyright ©1994, American Library Association. All rights reserved

Library Journal

Reviewed by Nancy Pearl, Washington Ctr. for the Book, Seattle

The stock market crash of 1987 brings an end to the good life that Alison and Sandy Koff have enjoyed during the 1980s. Not only do they lose all their money, but Sandy decides to return to his first wife. Alison can’t make ends meet with her part-time job as a reporter for the local newspaper, so she goes to work as a maid for Melanie Moloney, the celebrity writer who’s in town to dig up the dirt on Senator Alistair Downs, the subject of her next tell-all biography. When Alison finds Melanie murdered, she’s the main suspect, but others had a good reason to kill Melanie, including Downs himself, his daughter Bethany, and Cullie Harrington, an architectural photographer and Alison’s new love. Although readers will figure out whodunit long before Alison does, this sexy and humorous first novel will be enjoyed by fans of Susan Isaacs’s After All These Years and Judith Viorst’s Murdering Mr. Monti.

Inspiration

My first novel, Cha Cha Cha, was published in hardcover by Kensington Books in the summer of 1994 – a thrilling experience for me, as I had never dreamed I would write a novel, much less get one published.

I was living in Fairfield County, Connecticut, and working as a freelance writer when the idea for the story popped into my head. It was the mid-eighties – the Reagan “go-go” years – when people seemed to have lots of money and even more lavish ways of spending it. Enormous houses were sprouting up all around me, some of them with indoor squash courts and bowling alleys, even a few moats and turrets. I said to myself, Some day the debt is going to come due and all this prosperity will evaporate. Which it did on October 19, 1987, the day the stock market crashed.

I thought, what if you were one of the people who lost everything?

And then I thought, what if you were a wealthy suburban princess who lived in a mansion and never had to work and your biggest challenge was getting to your manicure on time? What if you lost everything?

That’s the setup for Cha Cha Cha, a social satire about our excesses and pretensions. After the heroine’s husband loses all their money in the stock market crash and leaves her for his first wife, she’s stuck in a house she can’t afford and can’t sell and doesn’t have any means of supporting herself – until she answers an ad for a maid. Without telling her fancy friends or her demanding mother about her new job, she packs her Pledge, her Windex and her Fantastik into her Porsche and goes to work. When her employer gets murdered and she becomes the prime suspect, she discovers an inner strength she never knew she had – and finds love in the process.

Dubbed a comic mystery-romance, Cha Cha Cha was a selection of the Literary Guild and Doubleday Book Club and was optioned for a television movie by Columbia/TriStar. It also landed me on the “Today” show. Not a bad start for a fledgling novelist!

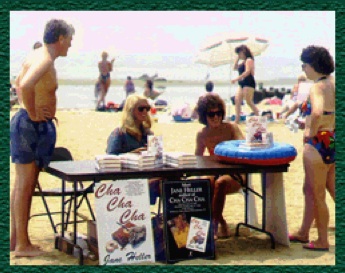

Since so many of the reviews for Cha Cha Cha declared the book a “beach read,” I decided to embark on the first-ever “beach author tour.” Instead of doing traditional bookstore signings, I appeared at beaches throughout Connecticut and signed copies and chatted with sunbathers.

It was great fun. I’m still shaking the sand out of my shoes!

Read the First Chapter

Clean Sweep (Formerly Cha Cha Cha)

Chapter One

On October 19, 1987, while I was sitting in Monsieur Mark’s Beauty Salon having my legs waxed, my nails polished, and my hair blown dry, the stock market crashed.

Of course, I didn’t find out about it until later in the day, when my husband, Sandy, appeared in my bathroom, just as I was stepping into a nice hot jacuzzi, and delivered the bulletin that we were broke. Just like that. Monday morning we had money, Monday night we did not. Monday morning I was a suburban princess on her way to a manicure, Monday night I was a desperate woman on her way to losing her husband, her home, and her job — and to becoming a murder suspect, of all things. What a difference a day makes.

I remember Black Monday as if it were last Monday. Black Monday. Stock Market Crash Monday. Say Goodbye to the Good Life Monday. Sandy had been speculating in the market on margin and had left himself exposed to potentially big losses if the market were to crash, which, of course, it did on that fateful October day.

“It’s gone!” Sandy had yelled, grabbing me by my bare shoulders as I stood knee-deep in swirling hot water.

“What’s gone?” I asked, looking down over my nakedness to make sure I hadn’t lost one of my body parts.

“Everything.” He sat on the edge of the tub with his head in his hands and mumbled something.

“I can’t hear you,” I said. The motor of the jacuzzi was drowning him out.

“Our money’s gone,” he said and began to sob.

I had never seen Sandy cry, so I was more than a bit alarmed. “What do you mean, ‘Our money’s gone’? Tell me what happened.”

“The stock market crashed, that’s what happened. We lost it. There’s nothing left.”

“How can that be?”

“It just is. And what is, is.” Sandy had taken a course in est in the mid-seventies and resorted to est-speak whenever he was under stress.

“But Sandy, all our money isn’t in the stock market. We have Money Market Funds and Treasury Bills and IRA accounts.”

“Not anymore. I converted all of that to stocks months ago.”

“You what?” Suddenly, I thought I might hurl my lunch right into the jacuzzi. All our money was in the stock market? The stock market crashed? We were broke? It was too much to bear. Quick! A joke! A joke! When in pain, make a joke, Alison. That’s always been your credo. Think of something amusing to make it all go away. Crack yourself up so you won’t have to feel anything. “Sandy,” I ventured. “What’s the definition of an economic advisor?” My husband gave me a disbelieving stare. “Someone who wanted to get into accounting, but didn’t have the personality.” I waited for him to get the joke. He didn’t; he looked at me as if I’d lost my mind. But I hadn’t lost my mind, just my money. Sandy’s money. The very money I’d married him for.

“Alison,” he said as patiently as possible, realizing how traumatized I must be to tell a joke at a time like this. “It’s true. All our money was in the market, and the market crashed today. Try to deal with it. Like I am.”

I took a few slow, deep breaths. “Okay. Okay. I’m calm. I’m rational. So tell me: why on earth did you put all our money in the stock market?”

“You never complained about the way I managed our money in the past.”

“And I’m not complaining now. I’m just trying to ‘deal with it,’ as you say. So tell me why you put everything we had in the stock market.”

“Because I was doing well in the market. I was making money for us — so much money that I decided to put our assets where I could really keep an eye on them.”

“But Sandy, you’re not an investment banker. You’re a retailer. You sell clothes and shoes and underwear.” My husband ran Koff’s, our town’s biggest and oldest department store.

‘Yeah, but all the guys are in the market now, Alison. Look at Bert Gorman and Alan Lutz. Bert may be a dermatologist but he calls his own trades. So does Alan and he’s a dentist. It’s not that big

a deal.”

“Not that big a deal? You tell me you’ve lost all our money and it’s not that big a deal?” My face was flushed and my legs were numb from standing in the hot jacuzzi water for so long. I climbed out of the tub and wrapped myself in one of the Adrienne Vitadini bath towels I’d bought at Bloomingdale’s. Then I waited for Sandy to say something psychological, something est-like, the way he usually did when there was trouble.

“All right. I fucked up,” he said finally. “But I’m owning up to it. I’m getting in touch with my pain, my guilt, and my shame. In fact, I’m getting so in touch with my shame that I’ve decided we should leave town. I can’t face people whispering about me in restaurants.”

“Leave Layton? You must be kidding.” A rural yet sophisticated Connecticut town nestled along the shores of the Long Island Sound, about an hour and fifteen minutes from Manhattan, Layton had been my home all my life. “We can’t leave Layton, Sandy. We live here. Our parents live here. And what about your job at Koff’s? The store’s a Layton institution. A gold mine. So don’t worry. You’ll make our money back in no time.”

“Haven’t you heard a word I said, Alison? The stock market went under! You think the store won’t go under next? You think people will have money to spend on designer clothes now? Come on, kid. Get real.”

I was real, kid. That was the problem. Try as I might, I couldn’t escape the awful reality that our “abundant life,” as my favorite magazine Town & Country called it, was about to be over.

Of course, Sandy was right when he predicted that the stock market crash would turn Koff’s’ business to shit. Thanks to a skittish economy and an even more skittish consumer, his income from Koff’s fell off dramatically. So did his spirits. He became utterly despondent over the downturn his finances had taken, and his despondency sent him back into therapy with Dr. Weinblatt, the psychologist he’d consulted when his first marriage broke up.

Apparently, Dr. Weinblatt made Sandy nostalgic for the good old days of that first marriage, because ten months after Black Monday stripped me of whatever sense of security I had, Sandy announced he was leaving me for his first wife.

It happened on a Tuesday night in August, an evening I came to call Black Tuesday. Sandy and I were having Chinese take-out food for dinner. We always had Chinese take-out food for dinner on Tuesday nights because Tuesday was Sandy’s therapy night. Some husbands have their bowling night; my husband had his therapy night.

Sandy preferred eating at home after therapy. He said he felt too “exposed” after his sessions with Dr. Weinblatt to go to a restaurant where people would be scrutinizing his every move. Sandy suffered not only from an aversion to being scrutinized, but from a delusion that people in restaurants found him interesting enough to scrutinize.

There was a decent Chinese restaurant right next door to Dr. Weinblatt’s office, so our routine on Tuesday nights was for Sandy to stop at the Golden Lotus before his session, place our order, pick up the food after his fifty minutes with Dr. Weinblatt, and bring it home.

“Home” was an 18-room, 7,200-square-foot brick Georgian colonial. No, the house didn’t have water views, but it was considered one of Layton’s prime properties because of its four-plus acres and numerous outbuildings — “dependencies,” the realtors called them. They consisted of a guest cottage, staff apartment, and party barn, none of which we had used in months, as we no longer had any guests, staff, or parties.

When we bought the house in 1984, Sandy suggested we name it. “All estates have names,” he assured me. I was skeptical. I thought it was pretentious for a nouveau riche Jewish couple named Alison and Sandy Koff to try and act like old-money WASPS, who routinely gave their houses names like “The Hedges,” “Harmony Hill,” or “Tranquillity.” But we kicked around some possibilities one night and I started to get into the whole thing. Eventually, we settled on “Maplebark Manor,” a name that gave the century-old maple trees on the property the respect and recognition they deserved.

Maplebark Manor was decorated in Greed-Is-Good Eighties style. In other words, we spent an obscene amount of money on a well-known New York decorator, who made us feel so insecure about our taste in furnishings that we allowed him to transform our home into the chintz capital of the United States. Nancy Reagan created the slogan “Just Say No” for people who are tempted by drug pushers, but I think it’s equally appropriate for clients who are intimidated by their decorators.

Despite all the chintz, the house had many wonderful features — spacious bedrooms, each with its own bathroom and fireplace; baronial, high-ceilinged “public” rooms; and an enormous, eat-in kitchen, which, after our $50,000 renovation, boasted sparkling new floors, cabinets, counter tops, and state-of-the-art appliances but was supposed to look like it had been that way for generations. The room I loved most was on the second floor. It had once been used as a children’s wing, but we converted it into a large office for me. We had decided to postpone having children until we were older. I was thirty-four when we bought the house and Sandy had just turned forty — old enough, you’re probably thinking, but the trend among driven, I-want-what-I-want-when-l-want-it couples of the eighties was to wait until their child-bearing years were just about over, then try their overachieving hardest to get pregnant, become incensed when they couldn’t, divert the thousands of dollars they’d been spending on their houses, clothes, and cars to in vitro fertilization and fertility drugs (don’t let anyone tell you the drug of the eighties was cocaine it was Clomid), and then, when nothing worked, drive themselves even crazier trying to decide what to do next: adopt, join a Big Brother/Big Sister program, forget about children altogether or take a soothing trip to the Caribbean to think about all of the above.

The room that was now my office faced south, was flooded with sunshine most of the day, and overlooked our swimming pool, tennis court, and gardens. It was in this room that I wrote articles about celebrities. I was a freelance writer whose work appeared in the Layton Community Times, a twice-weekly newspaper serving the residents of Layton and neighboring towns.

Big deal, you’re probably thinking. So she writes for a dinky local paper. What kind of celebrities could she possibly get to interview?

Plenty, I promise you. First of all, Layton has its very own community playhouse that does revivals of the best Broadway shows, and I was the reporter who covered all the openings and interviewed all the stars. Second of all, Layton is home to dozens of famous people-movie stars, TV personalities, writers, rock stars, you name it-most of whom are only too happy to plug their latest ventures.

It was in my capacity as celebrity reporter for The Layton Community Times that I met Sandy Koff — Sanford Joshua Koff, the son of the Koff behind Koff’s Department Store, a retailer who was around long before the Gaps and Benettons came to town. The occasion for my interview with Sandy was the announcement in March of 1983 that his father was retiring and turning over complete control of the store to Sandy.

I looked forward to our meeting because I’d heard Sandy was newly divorced. I was newly divorced myself and living in the two-bedroom condo I had shared with my first husband, Roger, who had left me and his medical practice to become a G.O. at Club Med. Roger’s father owned a button business in Long Island and was very rich. As a result, Roger was very rich, which was why he could afford to become a doctor and then decide not to.

The day I met Sandy was a good hair day; my shoulder-length, brown locks, which have a tendency to frizz, had not done so. I remember looking at myself in the mirror that morning and thinking, Not too shabby, Alison.

Actually, I’m not bad-looking. I’m thin (size 6) but not profoundly flat-chested (size 34B), am of average height (5’5″), and have remarkably even features for a Jewish person (no hook nose). I have a raspy voice, big brown eyes, and freckles across my nose. People say I look like the actress Karen Allen, which means that I also look like the actresses Brooke Adams and Margot Kidder, because Karen Allen, Brooke Adams, and Margot Kidder look the same.

My interview with Sandy took place in his office on the second floor of Koff’s Department Store.

“Nice to meet you,” he said, getting up from his chair and stepping around his big desk to greet me. I could tell he was checking out my outfit and wondering if I’d bought it at Koff’s.

I explained the nature of my article to Sandy and we chatted about his plans for the store. I sensed that he was a very sincere person because of all the psychological things he said during our first forty-five minutes together. Psychological things like: “I’ve been struggling to get in touch with my conflicts about surpassing my father.” And: “I have a primal urge to succeed as well as a subconscious wish to sabotage my success.” Not having had much exposure to psychology, I assumed that people who spoke in psychological terms were more open and trustworthy than people who didn’t. And, God knows, after having been raised by a mother whose idea of openness was never telling people her real age, and after having been married to a man whose idea of trust was leaving it to his secretary to tell me he was divorcing me, I was in the market for an open and trustworthy person.

I responded positively to Sandy’s appearance, too. He had a nice smile, with big white teeth that positively shone — a smile that broke up his long, thin, somber, Stan Laurel face and gave it some warmth. He also had a long, thin nose, long, thin fingers that had little black hairs growing around the knuckles and were manicured, and a long, thin body. As a matter of fact, everything about Sandy Koff was long and thin, except his very dark hair, which was short and thin, and his penis, which was long and fat. (More on that later.) He wasn’t your basic leading man, but I found him attractive in a Tony-Perkins-with-a-receding-hairline sort of way. I was particularly taken with his Adam’s apple, which bobbed up and down with such ferocity that I couldn’t take my eyes off it.

The other thing I noticed about Sandy that first day was how tan he was for the middle of March. He told me that he had just come back from Malliouhana, the resort in the Caribbean that used to be a little-known hideaway for sleek and sophisticated Europeans but was now, after being featured on “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous,” the vacation-spot-of-the-moment for the Rolex set, i.e. suburban doctors, lawyers, and garmentos. If you were on the beach at Malliouhana and yelled, “Is anyone here named Irving?,” every man in the place would say yes.

Sandy and I started dating right after that meeting in his office. He took me to lunch. He took me to dinner. He took me to sporting events. He took me to romantic little inns in Vermont. He introduced me to his friends. He introduced me to his parents. He even introduced me to his “physical catalyst,” which is what he called his personal trainer, who came to his house three mornings a week and showed him how to pump iron. Before I knew it, we had memorized each other’s phone number and given each other intimate little nicknames (my name for Sandy was Basset, because he reminded me of a basset hound; his name for me was Allergy, because the word sounded like Alison and because I apparently got under his skin like a pesky rash). Before I knew it, we had told each other juicy and disgusting things about our first spouses. Before I knew it, we had grown comfortable with each other, especially in bed: I no longer slept in the nude, he no longer asked me to sleep in the nude; I no longer acted as if I enjoyed giving him a blow job, he no longer acted as if he didn’t notice that I didn’t enjoy giving him a blow job. Before we knew it, we were an eighties couple in love.

What about passion, you ask? I wasn’t looking for passion then. I just wanted some certainty in my life-some guarantee that the man I married was loaded. This I learned from my mother, who told me over and over that a man wasn’t to be trusted unless he had money; that he wasn’t worthy of respect unless he had money; that he certainly wasn’t marriage material unless he had money — preferably inherited and earned. After years of such brainwashing, the best I could deduce about men was that it was okay to harbor a secret sexual attraction for a gas station attendant as long as the guy you married owned the pumps.

So I married Sandy Koff, who had money, in 1984. He seemed very happy. So did my mother. Two out of three was pretty good, I thought, which tells you something about my level of expectation.

We sold my condo and lived briefly in Sandy’s six-bedroom house on the water, which he had rented after his first wife kicked him out of their five-bedroom house on the water. Then we bought Maplebark Manor and moved in there. Life was sweet. Sandy ran Koff’s Department Store, I wrote newspaper articles about the famous and nearly famous. We wore expensive clothes, drove expensive cars, ate in expensive restaurants, and indulged in just enough lovemaking to keep our sex organs from atrophying. I discovered the joys of gardening, Sandy discovered the thrill of speculating in the stock market. I bought all of Martha Stewart’s books so I could learn how to throw parties, Sandy bought a computer so he could keep track of his stock transactions. We had friends, we had staff, we had money-until Black Monday, the day we lost it all. Oh, well, we still have each other, I consoled myself during the next few months. Then came Black Tuesday, the day Sandy came home from Dr. Weinblatt’s office with more than Chinese take-out food on his mind.

“I’m home,” he’d called through the intercom in the kitchen. We had installed intercoms on every floor of Maplebark Manor so that we never had to raise our voices.

“I’ll be right down,” I said through the intercom in my office on the second floor. It was seven-thirty, and I’d spent the past few hours working on an article about June Allyson, who had come to Layton not only to promote Depend Undergarments, but also to star in South Pacific, currently in production at the Layton Community Playhouse.

I hurried down the back staircase and entered the kitchen, where Sandy was unpacking little white boxes of Chinese food and spooning their contents into the pretty Depression glass bowls I’d picked up at an auction at Sotheby’s. He had already changed into his robe and slippers, and he appeared to be smiling, which is something I hadn’t seen him do in months.

“You’re in a good mood,” I said cheerfully as we carried the food, placemats, napkins, and silverware into the glass-enclosed breakfast room off the kitchen. We sat down across from each other at the round butcher-block table and started to dig in.

“Egg roll?” Sandy asked, offering me one of the items from the Pu Pu Platter.

“No thanks,” I answered, content with my sesame noodles for the time being. “So tell me why you’re in such a good mood. Is business up at the store?”

“No,” Sandy said with a mouth full of egg roll. “It has nothing to do with the store. It has to do with Soozie.”

“Soozie?” I asked sweetly, making a real effort not to let bitchiness creep into my voice. Soozie was Sandy’s ex-wife. She was also a caterer who, unlike my idol, Martha Stewart, didn’t have much of a head for business. Yes, she knew how to cook, as Sandy never ceased to remind me every time I tried to make anything in puff pastry and failed. But she didn’t have a clue how to market herself. Consequently, she was a caterer with few parties to cater. She had divorced Sandy because she had wanted to “spread her wings and soar.” From what I heard, she’d been doing plenty of spreading, all right, but it had nothing to do with her wings. Not that I cared how Sandy’s ex-wife spent her free time, mind you, just as long as it wasn’t with Sandy.

“I was going to wait until we finished dinner,” Sandy said, setting his fork down on his plate, reaching across the table to take my fork out of my hand and wrapping both my hands in his. I knew something big was coming, but I honestly had no idea what. “Allergy, I feel really good about myself now that I have an awareness of where I was coming from in terms of my feelings for you.”

He paused. I stared. Had he always talked like that? Had I never noticed how ridiculous he sounded?

“Allergy,” he continued. “I feel so close to you, now that I can put a label on your role in my life.” Another pause, then a deep breath, then a big smile. “You were my transitional woman.”

I stopped chewing. The sesame noodles that had tasted so good seconds before suddenly turned to cardboard. My heart began to beat faster as I waited for Sandy to finish his speech. I knew there was more. There always is.

“The thing is,” Sandy went on, getting up from his chair to put his arm around me, “Soozie still loves me and wants me back, and I still love her and want her back.”

Quick! Think of a joke! I thought as I struggled to comprehend what my husband was telling me.

What was he telling me? That he’d been seeing Soozie behind my back? That the two of them were lovers again? That he’d loved her all along and only married me out of loneliness or boredom? That I was a failure as a wife, as a woman, as a cook? That he was leaving me forever? That I was going to be alone again?

I was tempted to heave my plate of Chinese food at Sandy, I really was. The image of that thick, tan sauce dripping down his fluffy white Ralph Lauren terry-cloth robe, the one with the “family crest” on the front pocket, was mighty appealing. But I was too distraught to clean up the mess, and I was much too compulsive to leave it for Maria, our Peruvian housekeeper, who never found a speck of dirt when she arrived each morning because I always cleaned the house before she got there.

Quick! A joke! A joke! My eyes burned with hurt and anger, but I willed myself not to cry. Never let ’em see you sweat. Isn’t that what the commercial says?

Sandy, my husband. just look at him, I thought. What a pitiful sight. He graduated with honors from Columbia University and was at the top of his class at NYU Business School, so he can’t be a complete idiot, and yet listen to how he talks. Look at how he looks. He combs his three remaining hairs clear across his prematurely balding head and he thinks he’s fooling everybody. We all know you’re going bald, asshole. And Soozie, the caterer-whore. Of all the women to be left for. Soozie, whose real first name is the perfectly acceptable Diane but who insists that everyone call her Soozie.

“I know you must be devastated,” Sandy said, getting up from the table and wrapping me in his arms.

Devastated? Devastated? I thought, trying desperately to conceal my panic. Don’t let your husband think you’re dependent on him, my mother always said. Never let him know how much you care. Always make him guess. Keep your real feelings to yourself. Never wear your heart on your sleeve. Quick! A joke! A joke!

“Allergy? Are you all right? Say something,” Sandy said, looking genuinely concerned about me.

I took a deep breath and said two things to my faithless second husband. One was: ” Sandy, I think it’s good that you’re going back to Soozie, because I’ve been wanting to see other men for some time. You know my motto — ‘Never put all your eggs in one bastard.'” I waited for him to get the joke before proceeding with the second thing I said, which was: “And Sandy, if you ever call me Allergy again, I’ll tell everyone in Layton the truth about Soozie: that the secret ingredient in her ‘all natural’ chicken salad is MSG and that her ‘homemade’ cakes aren’t from scratch, they’re from a mix.”

Sandy scowled at me, shook his head, and walked out of the room. “You’re in denial,” he said. “Big-time denial.”

“Deny this,” I yelled as I gave him the finger. Then I wondered which was worse — losing your man or losing your meal ticket. I had just lost both, which was nothing to joke about.

Summary

What does a woman do when her husband loses everything in the stock market… then ditches her to go back to his first wife? If she’s Alison Waxman Koff, and she’s spent most of the 80’s living the Good Life in an extravagant mansion in an upscale Connecticut exurb, she sells her furs and starts doing her own nails. When that isn’t enough, she falls back on her one marketable skill: housecleaning. When that ends in mayhem and the murder of a bestselling sleaze biographer, Alison finds herself with yet another role to play: prime suspect. Suspense meets romance meets zany comedy in Jane Heller’s hard-hitting and hilarious debut novel about love and survival in the ’90s. Alison Waxman Koff is a true heroine for our times as she scrambles to keep in step with a changing world and to find love with a man who might just turn out to be Prince Charming after all.